Last week, the U.S. Labor Department reported that employers added 288,000 jobs in June, which lowered the unemployment rate to 6.1 percent, the lowest since September 2008. As reported in the New York Times:

Factoring in June’s increase and upward revisions for estimated hiring in April and May, employers added an average of 231,000 workers a month in the first half of 2014, the best six-month run since the spring of 2006. “We’re clicking on all cylinders in terms of job growth,” said Dean Maki, chief United States economist at Barclays.

Just as significant as the headline figures, Mr. Maki said, is that June’s hiring was broad-based, as industries as varied as health care, manufacturing, financial services and retailing all added workers.

But despite the overall good news for the job market, there’s one industry that’s still struggling to fill job vacancies: trucking.

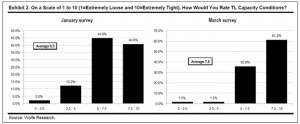

According to the American Trucking Associations, “the industry needs to find an average of roughly 96,000 new drivers annually to keep pace with demand. If freight demand grows as it is projected to, the driver shortage could balloon to nearly 240,000 drivers by 2022.” And as the chart below from Wolfe Research shows (click to enlarge), shippers are seeing truckload capacity tightening, which will cause rates to rise.

The driver shortage story is not new, but it’s arguably getting worse. An article in yesterday’s Wall Street Journal highlights the current environment. Here are a few excerpts from the article (emphasis mine):

Copeland Trucking, a family-owned company with about 50 trucks, is turning away business because of unfilled openings. The Minnesota-based firm’s $9 million a year in revenue “could go to $13 million or $14 million overnight if I could put drivers in those trucks,” said Charlie Hoag, manager of Copeland’s terminal in Des Moines, Iowa.

Trucking firms, while accustomed to high driver turnover, say hiring is tougher than ever. “It’s probably the most difficult recruiting environment…I’ve seen in my 26 years in the business,” said Scott McLaughlin, president of Stagecoach Cartage & Distribution LP, a family-owned firm in El Paso, Texas.

Some younger drivers are quitting because they don’t want to be away from home. For more than five years, Jacob Babcock, of Pinedale, Wyo., hauled hay to Texas and drove back to his home state with loads of pipe for gas fields. A year ago, he started a business repairing vehicles. Long-distance trucking “isn’t very family-friendly” said Mr. Babcock, who turns 30 this month…Exit interviews with drivers at Tennant Truck Lines reveal the pull of home outweighs earnings for many.

That last line sums it up for me: if you can’t pay people enough to become long-haul truck drivers — if the pull of home (of sleeping in your own bed and being with your family every night) is indeed greater than the pull of money, even when unemployment was above 8 percent — then what’s the solution to the driver shortage problem?

On the demand side, shippers have been doing what they can to minimize their dependence on long-haul trucking, including shifting more volume to rail, intermodal, and dedicated/private fleets, and making changes to packaging and investing in load optimization software to fit more products per case, pallet, and trailer, which results in fewer truckload shipments. And some shippers are starting to “walk the talk” on collaboration, sharing truckload capacity with other shippers, which enables continuous moves and reduces empty backhauls.

But what can carriers do, if Plan A — increasing wages and benefits, buying more modern and comfortable trucks, and using social media to recruit new drivers — is not helping much?

Can the industry create a business and operating model where drivers become a shared resource between carriers, enabling drivers, for example, to drive a load a certain distance, then switch at a meeting point, and drive a different load back home, all in one day? Are there any lessons or practices it can adopt from the airline industry, in how they manage pilot and crew schedules, and how they set up and manage codeshare agreements?

This might not be a workable idea, but my point is that a Plan B is needed, one that depends on increased collaboration between carriers (and between shippers and carriers, and shippers and shippers) and transforms the current operating model, because a great number of today’s drivers are retiring, and young people (no matter how much you pay them) would rather do a million other things than sit behind the wheel of a truck, and so the driver shortage will only get worse in the years ahead.

Or we could just grind it out until Plan C is ready to implement: driverless trucks.

Last week, Daimler was the latest manufacturer to showcase its self-driving truck, the Mercedes-Benz Future Truck 2025. While not completely driverless, it’s certainly a step in that direction. This follows recent news from the Netherlands, where according to a Reuters report, “self-driving trucks could begin delivering goods from Rotterdam, Europe’s largest port, to other Dutch cities within five years under a plan by a group of logistics and technology companies [a consortium including the industry group Transport and Logistics Netherlands, DAF Trucks, Rotterdam Port and the Netherlands Organisation for Applied Scientific Research].”

The only way to solve the driver shortage problem is through innovation. It’s already happening on the equipment side with the development of self-driving trucks. The time has also come, I believe, to innovate the trucking industry business model and processes. I’m not smart enough to know how to do it exactly, but as drivers become more of a scarce resource, I do know that maintaining the status quo will become untenable.

For related commentary, read the following:

- Daddy, What Was a Truck Driver? (Wall Street Journal – sub. req’d)

- Would Robot Drivers Check Facebook While Driving?

- What is the Future of Truckload Transportation?

- Beware, Driverless Cars are Everywhere!