Are manufacturers and retailers “joint employers” of the contract workers hired by their third-party logistics (3PL) partners?

Last week’s decision by the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) in the Browning-Ferris case opens the door for this new operating reality — and the costs and risks involved. As reported in The Hill:

At issue in the case was whether Browning-Ferris was responsible for the treatment of contracted employees. The Houston-based company hired Leadpoint Business Services to staff a recycling facility in California.

The labor board determined Browning-Ferris should be considered a “joint employer” with the Phoenix-based staffing agency. As a result, the company can be pulled into collective bargaining negotiations with those employees and held liable for any labor violations committed against them.

The NLRB ruling is a sharp departure from previous decisions that stated companies were only responsible for employees who were under their direct control. Without the power to set hours, wages or job responsibilities, the earlier rulings held, companies could not be held responsible for the labor practices of the contractors.

The Wall Street Journal provided some details on the working relationship between Browning-Ferris and Leadpoint, which is similar to how many 3PLs and customers work, especially in warehousing operations:

Browning-Ferris and Leadpoint employed separate supervisors and maintained distinct human resource departments. Leadpoint recruited, interviewed, hired and trained employees. The subcontractor also chose which workers to dispatch to the recyclery and assigned personnel to specific posts. Leadpoint unilaterally determined compensation and retained sole responsibility to discipline, review and fire workers.

The terms and conditions of Browning-Ferris’s relationship with Leadpoint are typical for innumerable American business contracts. Yet the majority [at the NLRB] asserts that Browning-Ferris exercised indirect control over the wages of Leadpoint workers by agreeing to pay the subcontractor a specified mark-up, among other dubious claims. Potentially, this NLRB ruling could extend to any business that uses a subcontractor or temp agency.

There’s already a joint employer precedent in the logistics industry. Back in 2013, Walmart was added as a defendant in a lawsuit brought against Schneider Logistics by temporary warehouse workers. According to a Marketplace article:

This particular warehouse [in Mira Loma, California] is operated for Walmart by a big national company called Schneider Logistics. The workers allege massive wage-theft and other serious violations — like failing to pay proper wages and overtime. The California Labor Department issued over $1 million in fines in late 2011, just before the lawsuit was initially filed. It covers a potential class of approximately 1,800 workers.

What is novel about this case (Carrillo v. Schneider Logistics) is that the workers don’t work for Walmart directly. Rather, they’re part of a big, and growing, reservoir of low-wage contract workers, sometimes called “permatemps.” This is the first time, the labor-lawyers say, that Walmart has been sued for work done by its contracted laborers.

In May 2014, Walmart and Schneider Logistics settled with the workers for $21 million, with Schneider reportedly paying the total amount without any contribution from Walmart.

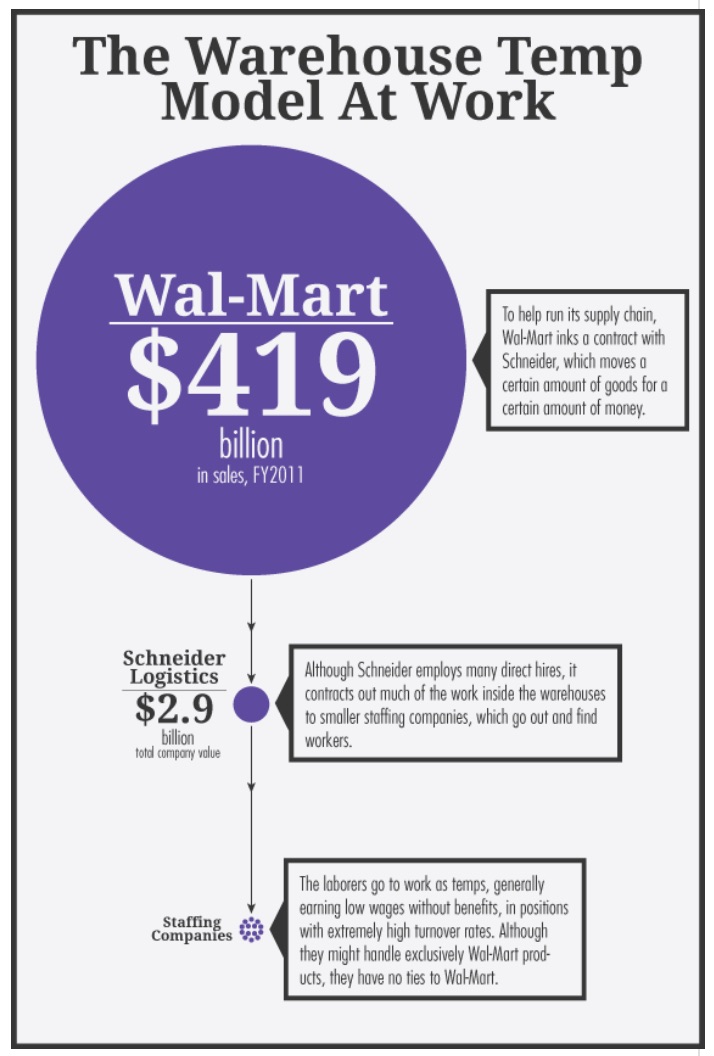

The use of temporary workers is very common in the 3PL industry, and the practice has led to criticism over worker pay, treatment, and safety. For example, see the long article by Dave Jamieson published in The Huffington Post (December 20, 2011): The New Blue Collar: Temporary Work, Lasting Poverty And The American Warehouse. The following infographic from the article outlines the structure of many 3PL-customer relationships with regards to temporary labor:

The bottom line: Despite growing automation, labor remains a critical component of logistics operations. As the Browning-Ferris case illustrates, as well as others focused on whether drivers are independent contractors or employees (see FedEx $228 million settlement and Uber case in California), the traditional definitions of “employer” and “employee” are being challenged by workers in the logistics industry, and the outcome could significantly impact the structure of 3PL-customer relationships. If you haven’t been paying attention to this trend, it’s time to get the conversation started, both internally and with your 3PL partners.

Do you believe this NLRB decision will have a significant impact on the 3PL industry? If so, what should 3PLs and customers do in response? Post a comment and share your perspective.