Earlier this month, an executive in our Indago supply chain research community submitted the following question:

“We see the future of transport moving toward electric and autonomous vehicles. However, the ownership, energy source, and labor relations will change drastically versus the current market structure of shippers, forwarders / brokers / 4PLs, and carriers. How do you see the future of transport evolving considering these factors?”

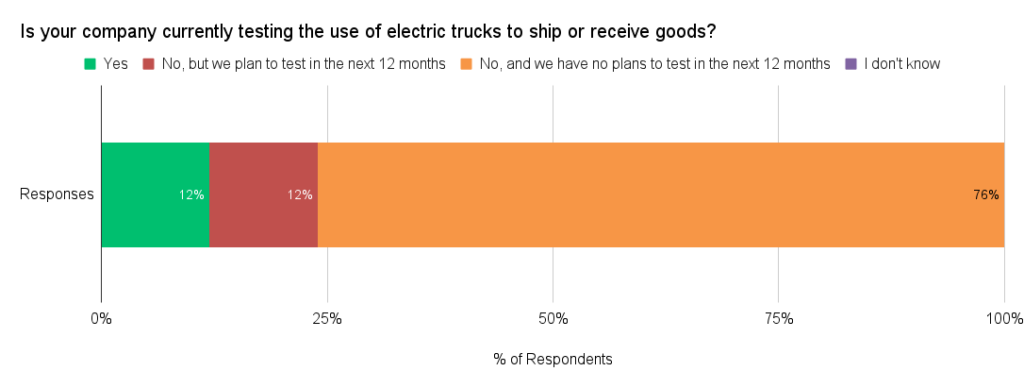

Based on this question, we surveyed our Indago members and only 12% of our member respondents are currently testing the use of electric trucks to ship or receive goods, and 76% have no plans to test them in the next 12 months.

“I do not agree with the statement ‘the future of transport will be electric and autonomous’,” said one Indago executive. “Truck transportation might convert to electric on some hauls, but not 100%. Given that major investment in road networks [will be required] to accommodate electric and autonomous vehicles in terms of infrastructures and security measures, I tend to believe this will not be a reality for many parts of the world.”

As for electric freight trucks, another executive commented:

“I believe the issue [that needs attention] is the ability for electricity providers/utility companies to [provide the amount of electricity] needed to support and sustain a fleet. Some areas will not have an issue [providing the necessary] infrastructure, others will face difficulties. I am also worried about certain geographies (e.g., Northeast USA) possibly not allowing fleets to charge during ‘peak consumer’ hours in the spring/summer. The risk of rolling blackouts or brownouts might require utility companies to shut down the power supply to large-scale users (i.e., fleet charging centers) during these times, which would affect a company’s transportation operations.”

A week after we published our report (available for Indago members to download), Andrew Boyle, ATA first vice chair and co-president of Massachusetts-based Boyle Transportation, testified before a Senate Environment and Public Works Subcommittee on the future of clean vehicles. Here is a 2-minute video highlighting his opening remarks, as shared by ATA:

Echoing the quote above about utilities not being able to provide enough electricity to charge electric freight trucks, Boyle shared a couple of anecdotes, as summarized in the ATA press release:

After one trucking company tried to electrify just 30 trucks at a terminal in Joliet, Illinois, local officials shut those plans down, saying they would draw more electricity than is needed to power the entire city.

A California company tried to electrify 12 forklifts. Not trucks, but forklifts. Local power utilities told them that’s not possible.

Boyle highlighted a few other challenges with electric freight trucks, including (as summarized in the press release):

- A clean diesel truck can spend 15 minutes fueling anywhere in the country and then travel about 1,200 miles before fueling again. In contrast, today’s long-haul battery electric trucks have a range of about 150-330 miles and can take up to 10 hours to charge.

- A new, clean-diesel long-haul tractor typically costs in the range of $180,000 to $200,000. A comparable battery-electric tractor costs upwards of $480,000. That $300,000 upcharge is cost-prohibitive for the overwhelming majority of motor carriers.

- Battery-electric trucks, which run on two approx. 8,000-lb. lithium iron batteries, are far heavier than their clean-diesel counterparts. Since trucks are subject to strict federal weight limits, mandating battery-electric will decrease the payload of each truck, putting more trucks on the road and increasing both traffic congestion and tailpipe emissions.

Simply put, replacing diesel trucks with electric ones for long-haul moves is not happening any time soon.

The “sweet spot” at the moment, beyond last-mile delivery, is using electric trucks for short-haul moves, particularly at ports and intermodal facilities. Last December, for example, Schneider announced that it was “taking delivery of nearly 100 Class 8 battery-electric vehicles (BEVs) at its intermodal operations in Southern California.” In February, Schneider’s CEO Mark Rourke was interviewed on CNBC’s “Squawk on the Street” about the future of EV trucks.

With regards to using electric trucks for long haul moves, he said:

“It’s going to take time. The range right now is about 200 to 240 miles depending upon terrain. So, it’ll be a while until we get battery electric trucks, but there’s other alternate fuels, like hydrogen, that may get us there sooner with still a zero emission, but it’s going to take a little bit [more time].”

Yet, as they announced back in June 2020, the California Air Resources Board “adopted a first-in-the-world rule requiring truck manufacturers to transition from diesel trucks and vans to electric zero-emission trucks beginning in 2024 [and] puts California on the path for an all zero-emission short-haul drayage fleet in ports and rail yards by 2035, and zero-emission ‘last-mile’ delivery trucks and vans by 2040.”

This is the same California that “finds itself on edge more than ever with a lingering fear: the threat of rolling blackouts for years to come,” as Ivan Penn reported in a September 2022 New York Times article titled, “Dodging Blackouts, California Faces New Questions on Its Power Supply.”

So, I’m with the Indago supply chain executive quoted earlier. Even if the range, weight, and cost challenges associated with electric freight trucks can be overcome, our electric utilities might crumble under the added demand for electricity, especially when you factor in the drive to replace gasoline consumer cars with electric ones, and the push in some states to replace natural gas appliances with electric ones.

What do you think?