Last week, while I was at the beach flying a kite, Elon Musk (founder of Paypal, Tesla Motors, and Space X) introduced his vision for a fifth mode of transportation: a Hyperloop, which would allow passengers to travel from Los Angeles to San Francisco in 35 minutes, traveling at a top speed of almost 800 miles per hour.

If you’re a tech junkie, you can read the fifty-seven page technical paper that Musk published, but here’s the idea in a nutshell (as described in Wikipedia):

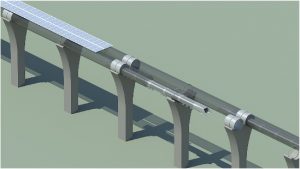

A hyperloop employs an elevated tube through which capsules move. The tube is partially evacuated to reduce friction. The capsule rides on a cushion of air forced through multiple openings at the capsule’s bottom, further reducing friction. The capsules would be propelled by linear induction motors placed at intervals along the route.

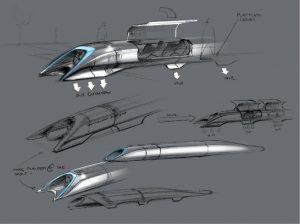

And here are some images from the technical document:

Although the focus is primarily on passenger travel, a Hyperloop could conceivably be used for freight movements too.

So far, Hyperloop has been met with a mix of curiosity and skepticism, along with spoofs and punchlines from late-night comedians.

Considering his past successes, I will give Elon Musk the benefit of the doubt that he can build a Hyperloop, but probably for a whole lot more than the $6 billion he currently estimates. The bigger question for me is, do we really need it? Is this another example of us going after the “next new shiny thing” versus investing to improve what we currently have? These are the same questions I raised back in March in “Forget Innovation, Just Execute Better.”

Musk indirectly asks the same question in the second page of his paper, where he writes:

If we are to make a massive investment in a new transportation system, then the return should by rights be equally massive. Compared to the alternatives, it should ideally be:

- Safer

- Faster

- Lower cost

- More convenient

- Immune to weather

- Sustainably self-powering

- Resistant to Earthquakes

- Not disruptive to those along the route

High-speed rail fails this test, according to Musk and others. And drones, which I view as a potential new transportation mode, probably fails the test too.

Here’s the bottom line for me: I firmly believe in the value and importance of innovation — in technology, medicine, transportation, business models, and other areas. In fact, that’s the reason why I became an engineer. But I also believe that the pursuit of innovation (specifically, the pursuit of something completely new) often causes us to overlook or under-prioritize the opportunities that exist to create significant value by better utilizing and optimizing the solutions we already have in place today. In trucking, for example, we see the opportunity every day: your private fleet comes back empty from an outbound delivery while a common carrier follows behind with inbound goods. Or a common carrier makes an inbound delivery and heads out empty, while another truck (perhaps from the same carrier) heads out in the same direction loaded with outbound goods.

What could the industry achieve if manufacturers and retailers actually “walked the talk” on collaboration? How much time and cost can we drive out of supply chains if there was less red tape, bureaucracy, and regulations? An article in the Wall Street Journal about the FAA’s NextGen project provides some insight. By using satellite-guided arrivals and departures at Seattle and other airports, Alaska Air saved $17.6 million and 200,000 gallons of fuel last year. However, according to a review by the Government Accountability Office, “the NextGen rollout has been hindered by bureaucracy, delays designing new navigation procedures and fear of conflicts with airport neighbors or environmentalists.”

Simply put, why bother trying to overcome the challenges of collaboration, red tape, poorly integrated systems, and bureaucracy that exist in supply chain management when you can just imagine something new and go after it?